We spoke before of the looming Recession and why I think it started yesterday, October 1 (Student Loan repayments) and other precipitating events (China invades Taiwan). Today, let’s look to see if the math supports the thesis.

For a precipitating event to have any meaning, the underlying conditions of the economy must be fertile for regressive action. In other words, the fundamentals must be weak enough for the event to matter. Are they? I think so, and I draw my conclusion from 6 different numbers. See for yourself.

Money Supply (M1) and Core Inflation

When you inject more money into the economy during a one year period than it has had in the cumulative history of money, you’re going to have a problem. This is exactly what the Fed did to ease liquidity concerns when the economy ground to a halt during the COVID shutdown.

Anytime you put money into an economy that doesn’t originate in increased production, you create inflation. The more dollars, chasing the same (or sooooo much less) goods and services, means prices rise. That’s inflation. So, in essence, we injected more than $6T into the world economy (because every Central Bank on earth followed the Fed), but we didn’t increase world GDP by an equivalent sum, then inflation was the necessary and only result. Policymakers knew this, and knew that they would be scaring up both asset and labor rates, but either did it because they wanted to establish a new base level for those things, or they thought they could just as easily reverse it. They were wrong. Inflation remains sticky.

We heard early from the history’s worst Press Secretary that the Administration considers inflation “transitory.” This means that it will go away over time. How much time? Next question because we don’t know. But the reality is that the only way to bleed inflation out of the world economy is through a recession that increases by a drastic percentage the number of working people. This, in turn, should translate into lower wages, which in turn then leads to lower prices. And it takes forever to work its way through the system and quite frankly isn’t happening naturally at all.

So the Fed comes in and raises rates faster than any time in history and does so in a way that isn’t transparent or conducive to good economic planning. For this reason, many startups who were managing their growth businesses beautifully and according to plan, ran out of money and had nowhere to go to find it. They are closing up shop, selling off (my Family Office has bought two of them this year, and have another 3 in the crosshairs), and the innovation and jobs that go with them go away now.

And it isn’t working. The Fed only has 2 more raises that it can make before it literally bankrupts the Federal Government’s ability to pay interest on its own debt. But they are going to make those rate increases happen. Prime will be close to 9% by the end of this year, and will stay elevated for as long as it takes for mortgages to reset, lending rates to adjust, people to default on their homes, credit cards, and student loans, and the economy to suffer, because only then will inflation tick downwards.

People who think that rates will temporarily get high and then be reduced in 2024 and 2025 are probably not right. Reducing rates before inflation is tamed back to an acceptable 3% range simply compounds the problem. And the Fed knows it and is talking about it.

Liquidity is Being Drained from the Economy (M2)

Not to insult my readers, but if you don’t know the difference between M1 and M2, you aren’t alone. We learn about in college economics classes and never think about it again, but its literally the interaction between the two that matters in forecasting economic conditions. M1 is the liquid and easily spendable assets you can deposit in the bank. M2 is the investments you buy with M1.

Relatively recently in our financial history, the Fed has begun participating in buying M2 assets. Stocks, bonds, and any other financial instrument it thinks will help the economy chug along. In the past several months, though, it has begun to sell those assets off in the public markets … very quietly. At its peak, the Fed owned $9T of M2 assets. It’s now shedding assets to the tune of $1T per year. That’s the fastest reduction since inception of the program in 1960 and weaponization of the program in 2008.

It all sounds like mumbo-jumbo to most of us though, right? What does it mean? It means that the number one buyer of stocks, bonds, and other financial assets in the world has decided it doesn’t want to own them any more and is dumping them as fast as it possibly can without triggering a collapse and losing its money. It’s dumping those assets on a public who doesn’t understand the implications of the decision, who keep buying the assets with inflated dollars, because their “advisors” say that the stock market always goes up over time.

But think about this. Does more supply mean higher or lower prices? The more the Fed sells, the less appetite there is for what its selling and prices flatten and then adjust to oversupply. M2 tightening matters.

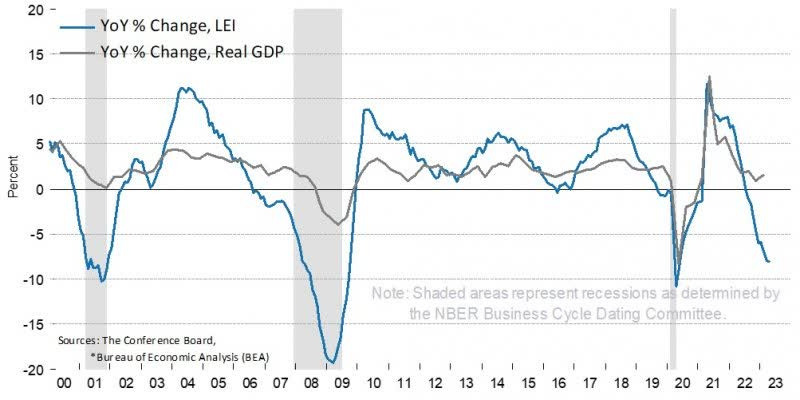

Leading Economic Indicators

The Council of Economic Advisors to the President look at a basket of 10 different ratios and measurements to gauge the near term rate of growth of the economy. They call this the LEI and its reported monthly on a monthly lag. The data is always 30 days old. It’s like driving down the street and using your rear-view mirror for navigation. Anytime the LEI index goes below zero, a recession is in the offing.

We spoke before about how only the Council can declare a recession and it has recently departed from its tried and true methodologies for doing so, preferring a “narrative driven approach,” double-speak for “we don’t want it to be a recession yet.” Too late, though, the numbers tell the tale.

The recession was indicated 4 months ago. It’s just waiting for the precipitating event.

Inverted Yield Curves

The U.S. Treasury finances federal government budget obligations by issuing various forms of debt. The $23 Trillion Treasury market includes Treasury bills with maturities from one month out to one year, notes from two years to 10 years, as well as 20- and 30-year bonds. The yield curve plots the yield of all Treasury securities.

Before we were so ably assisted in economic prognostication by the Council of Learned Nerds, Wall Street needed a rule of thumb measure of where we were headed. Typically, the curve slopes upwards because investors expect more compensation for taking on the risk that rising inflation will lower the expected return from owning longer-dated bonds. That means a 10-year note typically yields more than a two-year note because it has a longer duration. Yields move inversely to prices.

A steepening curve typically signals expectations of stronger economic activity, higher inflation, and higher interest rates. A flattening curve can mean the opposite: investors expect rate hikes in the near term and have lost confidence in the economy's growth outlook. An inverted yield curve means that investors are convinced that the economy will contract in the short term.

When 10 Years underperform 2 years, the yield curve has inverted and a recession is signaled. Guess what?

Bank Collapse

The last thing to take notice of is the very poor health of the banking industry. Banks are only as good as they loans they make, service and profit from. As the cost of capital increases (either from depositors, or from the Fed itself), the bank still has to make money and so adds its expected return to each note, grossing up the rate. If Prime is 7%, then the loan to an end-consumer is 8.5% so that the bank can make a profit. Nothing wrong with that. But …

If the things that borrowers want to borrow money for are now far less profitable, they simply won't borrow the money in the first place. This is a manageable situation for a bank. “Hey, we don’t have as many loans, so we don’t need as many people to make and service those loans.” No problem, scale up and down with volume.

If, however, those loans are adjustable and have moved to where the underlying asset no longer performs to meet the obligations, banks go from being lenders to operators and they hate that worse than anything. That means they loan $1m for a dry clear to expand his operation, the demand for dry cleaning dries up, the loan reprices to 9%, effectively doubling, the dry cleaner can’t make it work and hands his banker the keys. Now the banker is pressing shirts on Tuesdays instead of making loans until he can sell the asset, usually at a discount to what is owed. It’s the worst of all scenarios and we saw it in 2008, and we’ll start to see it a bit more in the coming months.

The real problem is that the banking system isn’t homogenous, although regulators never seem to understand that. Big banks (too big to fail banks), have a different set of economics than regional, or community banks. They can weather storms, largely because they have an implicit contract with the government for a rolling bailout when needed. The regionals don’t have this at all, and the community banks just get taken over by the FDIC and given away to other banks.

Remember Silicon Vally Bank? It had plenty of money to pay its depositors, but tied the money up in ways it couldn’t get to it when it absolutely had to have it. Most Regional banks are in that place now because they invested in long term T-bills whose pricing has dropped below what they paid for them. See the chart above and take a guess as to what they own. Now go ask them for your deposits back. They have to sell 10 year T-bills for a loss to give you your money back. How many times do you think they can do that before they fail?

When the recession hits, the regionals will be the banks to collapse, be taken over by the Federal government and consolidated into super-regionals, or sold off to the Big banks. Mark it down.

Super longwinded, I know, but you have to get the numbers on the table and see what they say. And they are saying “Yikes! Look out below!” In many conversations with people on this subject, I keep coming to the conclusion that I can make every argument that its coming, and I can’t find a single reason that it isn’t.

A good friend pointed out the real estate investments made properly can benefit in these conditions, and he’s right. Another friend pointed out that when governments respond to long-term recession, they go to war. Smart governments set the stage for those wars as soon as the indicators point to recession.

Now you overlay the charts above, paying special attention to the dates, and tell me that War with China, and War with Russia don’t line up perfectly with pulling the US out of recession in early 2025.

I feel like this is the longest awaited recession in my lifetime. The amount of money in the economy is preventing the normal cycle from happening and my fear is that it will create a bitter cold winter when it finally comes.

Thanks for a great write up on the subject.

Stay nimble, stay liquid...